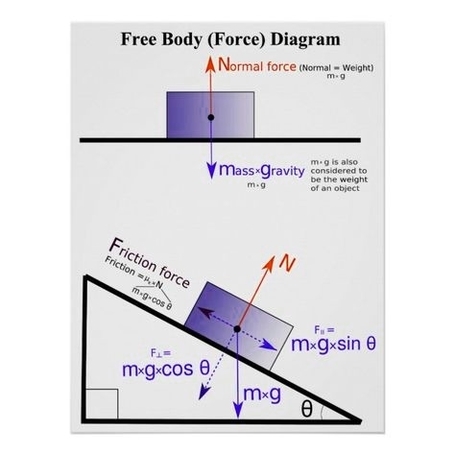

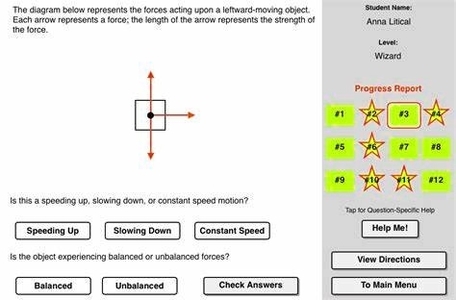

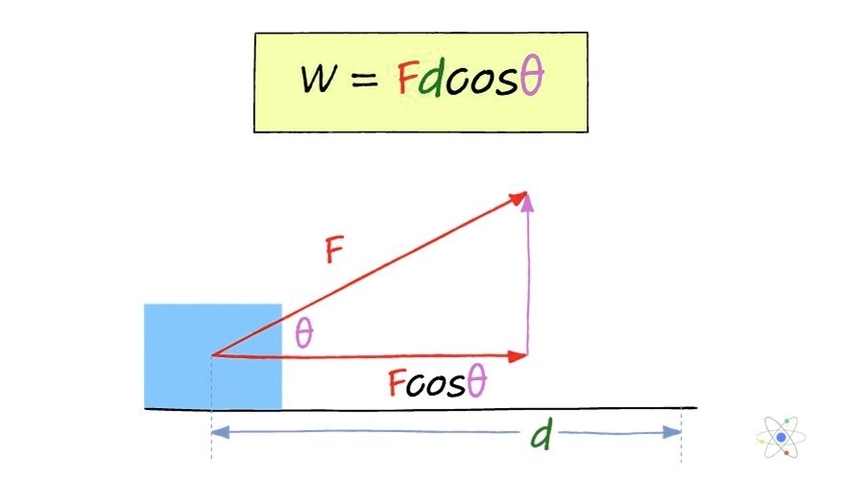

Free body force physics is a branch of physics that deals with the analysis of forces and moments acting on a body in a given situation. A free body diagram (FBD) is a graphical tool that helps to visualize and simplify the problem by showing only the relevant forces and their directions. Here is an example of a free body diagram for a block resting on a ramp:

“`latex

begin{tikzpicture}

% Draw the ramp

draw[thick] (0,0) — (4,2);

draw[dashed] (0,0) — (4,0);

draw[<->] (2,0) arc (0:26.6:2) node[midway,right] {$theta$};

% Draw the block

draw[fill=gray] (2.5,1.25) rectangle (3.5,2.25) node[midway] {$m$};

% Draw the forces

draw[->,red,thick] (3,2.25) — (3,3.25) node[above] {$F_N$};

draw[->,red,thick] (3,1.25) — (3,0.25) node[below] {$mg$};

draw[->,red,thick] (2.5,1.75) — (1.5,1.75) node[left] {$F_f$};

end{tikzpicture}

“`

In this diagram, the block has a mass $m$ and is subject to three forces: the normal force $F_N$, the weight $mg$, and the friction force $F_f$. The angle of the ramp is $theta$. The goal of free body force physics is to find the magnitude and direction of these forces, as well as the acceleration and motion of the block, using Newton’s laws of motion and some basic trigonometry.

One of the main principles of free body force physics is that the net force on a body is equal to its mass times its acceleration, or $sum F = ma$. This means that we can write equations for the horizontal and vertical components of the net